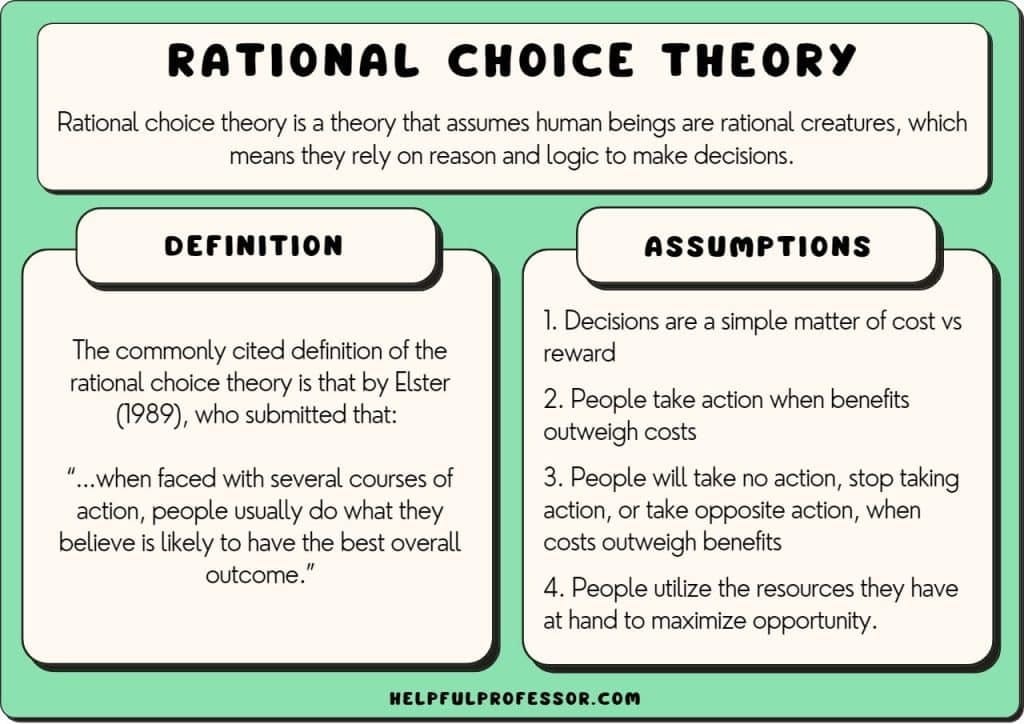

Standard economic theory is built upon the premise that people’s behavior is the result of logical reasoning and always prioritizing self interest. Adam Smith set down the foundational belief that men, I say men here because he didn’t consider women as economic actors, make decisions rationally, and prioritize their own wealth. This idealized economic decision maker described in rational choice theory has been called homo economicus.1

Behavioral economists confronted standard economic theory by recognizing that observed reality does not support the existence of homo economicus. Social and psychological factors influence human choice frequently more than simple rationalism and self interest. This remains a controversial shift in our understanding of economies. The best source of insight into the future is often what choices people made in the past and why.2

Human-centered design (HCD) operates on a similar belief that user behavior is dictated by a constellation of forces not just logic. It is an approach to making our world with consideration for what people do, not theorized rationale. It prioritizes people as they are with our confounding sparkle and spice. Universal Principles of Design was published over 20 years ago—a catalog of rationale on which to base design choices. People have produced many frustrating products by solely relying on such design principles without collaborating with users. Talking to people and observing what happens when you put your work in someone else’s hands is the way to amazing design outcomes. Human-centered design is a practice of humility—embracing that you alone cannot know all the answers.4

Methods of observing user behavior to reveal patterns and themes changed how we design information architectures (IA) and user experiences (UX). We accept that the variables at play for every product and every customer make following principles alone insufficient. Designing products by algorithm requires synthetic personas—the design version of homo economicus. The list of ‘it depends’ considerations and contexts will always too long and your product will land in the uncanny valley.

Added upon HCD, trauma-informed practices bring another set of principles and methods that increase our ability to make something that works well for more people. It is a more informed approach to design that prioritizes avoiding or mitigating harm. Advances in trauma science have yielded insight into the psychological, physiological, and social impacts of traumatic events that we can translate into design. When we understand that trauma increases phenomena like cognition errors, avoidance, and interpersonal challenges, we make it possible to design things that are a better experience for people living with these effects, whether as a temporary challenge or lifelong. For a thorough reading of the ways trauma may impact an individual, I recommend reading Chapter 3: Understanding the Impact of Trauma from Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Sciences.5

Trauma-informed design is designing for life. Through our lifetimes we will encounter trauma, live through crisis, watch those we love struggle and get through the unthinkable. Heck, There’s a whole industry out there documenting and cataloging the traumatic events happening in communities and nations. It’s called the news.

Trauma is… a coworker who was violently bullied frequently in high school, now panicking at a mandatory team retreat arranged with shared lodging.

Trauma is… a woman who doesn’t have access to health insurance struggling to change lanes for the hospital exit while her grand-baby screams with a high fever in the back seat.

Trauma is…living with sickle cell anemia.

Trauma is…human.

Just as accessibility features improve experiences for people with disabilities and those without, trauma informed approaches improve experiences for everyone, not just those in crisis. It’s not a specialized type of design. It’s design for real living people not idealized customers.

If you want to learn more about trauma-informed design and research, subscribe to this newsletter, and join our upcoming webinar, Introduction to Trauma-Informed Design and Research on November 6.

Book of the Week

If you are looking for examples of how to apply a trauma-informed approach to your work, from diverse points of view, this book is a great find. Bringing together designers who work with vulnerable populations as well as mental health practitioners, you’ll find many trauma-informed research techniques and guidance.

BehavioralEconomics.com. 2024. “Rational choice in Standard Economic Theory - Behavioral Economics Institute BehavioralEconomics.com.” Behavioral Economics Institute BehavioralEconomics.Com. November 7, 2024. https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/be-academy/courses/behavioral-economics-theory-and-practice/lessons/lesson-1-introduction/topic/rational-choice-in-standard-economic-theory/

Thaler., Richard H. n.d. Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Marufu, Archebold T. 2024. “Rational Choice Theory in Sociology (Examples and Criticism) (2025).” Helpful Professor (blog). June 13, 2024. https://helpfulprofessor.com/rational-choice-theory-sociology-examples-criticisms/.

Lidwell, William, Kritina Holden, and Jill Butler. 2010. Universal Principles of Design. 2nd ed. Beverly, MA: Rockport.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US). Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2014. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 57.) Chapter 3, Understanding the Impact of Trauma. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207191/.